John Greiner-Ferris, along with Kevin Mullins, is the co-founder of Boston Public Works Theater Company.

John Greiner-Ferris, along with Kevin Mullins, is the co-founder of Boston Public Works Theater Company. Just like the end of every year, with 2014 there’s the compulsion to sing a round of auld lang syne, and Boston Public Works Theater Company is no different. It was an extraordinary 2014 for us as we took the first steps to build a company then proceeded to launch our first season. Web sites, Facebook pages, Twitter accounts, digital launches and launch parties, Indiegogo campaigns were just some of the tactical projects that overlapped and gave credence to our fondness for saying that we are laying track in front of an oncoming locomotive. All of that will be covered in an email that will arrive in your mailbox tomorrow. In the meantime, I have a few things on my mind.

The Year That Really Was Two Years

While we’re ending a calendar year, it was two years ago—January, 2013—when Kevin Mullins, Max Mondi, who has since moved to New York, and I were talking in the Kitchen across from the BCA and got the idea to form a theater company based on 13P. That January, we started meeting at the Green Street Café in Cambridge a couple of times a month, and I don’t think we ever had any doubt that this—a new company composed of playwrights who produced their own work—wouldn’t happen. I bring this up only because maybe from the outside it looks easy to start a theater company. In truth, it’s an incredible amount of time, hard work, and sleepless nights, and while I maintain that self-production is a viable alternative to the traditional route to production, it isn’t for everyone. But for those playwrights who have the vision, tenacity, and passion, the rewards are incredible.

The Year That Really Was Two Years

While we’re ending a calendar year, it was two years ago—January, 2013—when Kevin Mullins, Max Mondi, who has since moved to New York, and I were talking in the Kitchen across from the BCA and got the idea to form a theater company based on 13P. That January, we started meeting at the Green Street Café in Cambridge a couple of times a month, and I don’t think we ever had any doubt that this—a new company composed of playwrights who produced their own work—wouldn’t happen. I bring this up only because maybe from the outside it looks easy to start a theater company. In truth, it’s an incredible amount of time, hard work, and sleepless nights, and while I maintain that self-production is a viable alternative to the traditional route to production, it isn’t for everyone. But for those playwrights who have the vision, tenacity, and passion, the rewards are incredible.

You Were The Reason For Our Successful Year

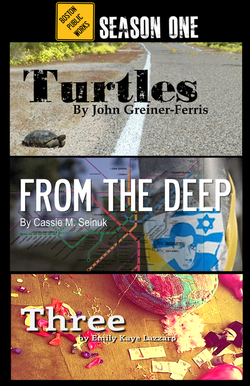

We had the passion, drive, and vision. But that took us only so far. If that were all we had, we would have failed miserably. The people who actually are responsible for the success BPW enjoyed this past year are the more than 400 family members, friends, and organizations who believed in what we were trying to accomplish and supported us. They donated hard dollars in a bad economy to fund our first season. Something I learned was that it’s very easy to get hits on a blog or likes on Facebook (clever headline writing from working in ad agencies works wonders!) What is really tough to do is convince people to finance your project, and our mission seemed to strike a chord with people: take control of your art, help other playwrights do the same, pay artists for their talent. The same goes for the people who came to our inaugural play, Turtles. On any given night, they could have gone anywhere, but they chose to see a new play produced by BPW. They responded enthusiastically to the work, and we want to continue our relationship with everyone who came throughout the rest of our season, consisting of From The Deep and Three.

We had the passion, drive, and vision. But that took us only so far. If that were all we had, we would have failed miserably. The people who actually are responsible for the success BPW enjoyed this past year are the more than 400 family members, friends, and organizations who believed in what we were trying to accomplish and supported us. They donated hard dollars in a bad economy to fund our first season. Something I learned was that it’s very easy to get hits on a blog or likes on Facebook (clever headline writing from working in ad agencies works wonders!) What is really tough to do is convince people to finance your project, and our mission seemed to strike a chord with people: take control of your art, help other playwrights do the same, pay artists for their talent. The same goes for the people who came to our inaugural play, Turtles. On any given night, they could have gone anywhere, but they chose to see a new play produced by BPW. They responded enthusiastically to the work, and we want to continue our relationship with everyone who came throughout the rest of our season, consisting of From The Deep and Three.

Eugene Delacroix's La Liberté guidant le peuple

Eugene Delacroix's La Liberté guidant le peuple BPW’s Not The First In Boston. We’re Not Even Close.

I would love to take credit for being a ground-breaking revolutionary in Boston, a la Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, leading playwrights to freedom through self-production. But, the fact of the matter is, I’ve been sitting in theaters for many years admiring other theater artists in Boston produce their own work, thinking, “Man, I want to do that, too.”

There is a tradition in Boston of self-production starting, for me at least, with Ryan Landry and his Gold Dust Orphans who has been producing his own work for at least a decade. Then there is Dawn Simmons and A. Nora Long at New Exhibition Room, John J. King and his Vaquero Playground, and Charlotte Meehan and Adara Meyers at Sleeping Weazel, all putting out their own work. This past October, three Boston playwrights self-produced full-length plays: my script, Turtles, by BPW, Pete Riesenberg and his Office of War Information produced his play, J.A.S.O.N. and Bill Doncaster produced his play, Two Boys Lost through his company, Stickball Productions. This isn’t a fad, and I would love to see seven or eight other companies like Boston Public Works producing original, full-length plays by Boston playwrights, along with individual companies like the ones Nora, Dawn, John, Ryan, Pete, Bill, Charlotte, and Adara have started.

For some reason, playwrights have been relegated to a rather impotent role in the traditional theater. While I’m certainly not discounting the traditional theater model, and I especially support the theaters in Boston too numerous to list here who do produce new work by local playwrights, my hope is that, through Boston Public Works, more playwrights can see the possibilities presented by self-production and simply see it as a viable alternative to the traditional method.

I would love to take credit for being a ground-breaking revolutionary in Boston, a la Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, leading playwrights to freedom through self-production. But, the fact of the matter is, I’ve been sitting in theaters for many years admiring other theater artists in Boston produce their own work, thinking, “Man, I want to do that, too.”

There is a tradition in Boston of self-production starting, for me at least, with Ryan Landry and his Gold Dust Orphans who has been producing his own work for at least a decade. Then there is Dawn Simmons and A. Nora Long at New Exhibition Room, John J. King and his Vaquero Playground, and Charlotte Meehan and Adara Meyers at Sleeping Weazel, all putting out their own work. This past October, three Boston playwrights self-produced full-length plays: my script, Turtles, by BPW, Pete Riesenberg and his Office of War Information produced his play, J.A.S.O.N. and Bill Doncaster produced his play, Two Boys Lost through his company, Stickball Productions. This isn’t a fad, and I would love to see seven or eight other companies like Boston Public Works producing original, full-length plays by Boston playwrights, along with individual companies like the ones Nora, Dawn, John, Ryan, Pete, Bill, Charlotte, and Adara have started.

For some reason, playwrights have been relegated to a rather impotent role in the traditional theater. While I’m certainly not discounting the traditional theater model, and I especially support the theaters in Boston too numerous to list here who do produce new work by local playwrights, my hope is that, through Boston Public Works, more playwrights can see the possibilities presented by self-production and simply see it as a viable alternative to the traditional method.